The Summer I Read

Or, How to Be a Woman Without Losing Your Mind (Read More Books)

I was fortunate enough to spend this summer strolling through Parisian side streets, traipsing on the cliffs of England, running through Danish forests, and lying on beaches in Italy. It was dreamy. It was, frankly, a hard-earned result of taking an enormous bet on myself and trusting my intuition.

During all of this wandering, I was constantly, voraciously, devouring books. I have become a big audiobook listener. This is a brave new world for me. I used to be a fiend for podcasts, but simply have no tolerance for them any more. Instead, I am more or less always reading. When I’m walking, running, washing dishes, brushing my teeth, folding laundry, staring at the wall — I am reading.

Women writers and their stories continue to find me. Or maybe I am finding them? I can’t tell. What I do know is that every book about motherhood, sex, desire, death, and reinvention, is shifting something for me. I am becoming a better writer because of these books. I am, I think, becoming a better person because of these books. Isn’t that ultimately the magic that reading affords us?

I blew through eighteen books in total this summer, but here are five books that cracked me wide open.

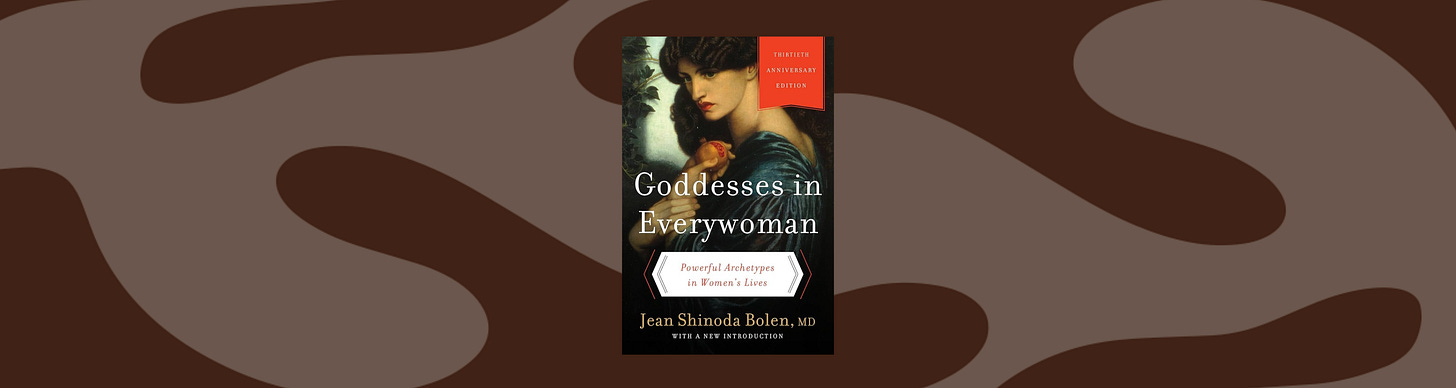

The Goddesses in Every Woman, Jean Shinoda Bolen

In the early weeks of summer, or the late weeks of spring, I finally finished reading The Goddesses in Every Woman. I had been nurturing a newfound interest in Jungian psychology, and the psychology of archetypes. This book highlights the seven primary Greek goddesses: Hera, Hestia, Aphrodite, Demeter, Persephone, Athena, and Artemis. Jean Shinoda Bolen is a Jungian psychiatrist whose work bridges mythology, psychology, and feminism to illuminate our inner lives and archetypal patterns. In this book, Bolen explores how each goddess — with her particular traits, desires, and shadows — appears in our lives as women.

For example, how Hera’s (The Wife) loyalty can harden into resentment when her devotion isn’t met. How Aphrodite’s (The Lover) creative and erotic power can become untethered when she seeks external validation instead of her internal radiance. How Athena’s (The Strategist) brilliance can detach her from emotion, and how Persephone’s (The Maiden) innocence, when unexamined, becomes a form of passivity mistaken for peace.

Reading this book is like encountering a mirror. Some reflections more familiar, and some more foreign, but all of them are inside of me in some way. I began to recognize the years I’d spent living from the archetype of Athena, driven by self-sufficiency, while neglecting the parts of me that crave sensuality, stillness and communion.

The book offers a language for multiplicity. My friends and I are constantly repeating the phrase, we women contain multitudes, and that is exactly what this book offers. Proof that we can be tender and cunning, restless and serene, virginal and feral.

Splinters, Leslie Jamison

I honestly can’t remember why or when I added Splinters to my Goodreads list, but thank god I did. I listened to it on audiobook while housesitting in a small coastal village in southwest England. Every day I walked along the cliffs, the wind biting at my face, Jamison’s voice in my ears. The story traces the aftermath of divorce and the uneasy rebirth of motherhood, creativity, and selfhood that follows rupture.

What immediately drew me to Jamison is her surgical precision. She’s claims to be uninterested in telling the cocktail-party version of her story, which I adore as a confessional writer myself. She offers the granular texture of her life: the small humiliations and banal fantasies.

Months after finishing this book, I still go back and reread passages. Like when she writes about conversations with women as scaffolding for the soul. “The version of myself made possible by conversations with friends was the self I most readily recognized,” she writes.

Splinters is a book about motherhood and divorce, but it’s also about reckoning with the gap between the story of love and the texture of actually living in it.

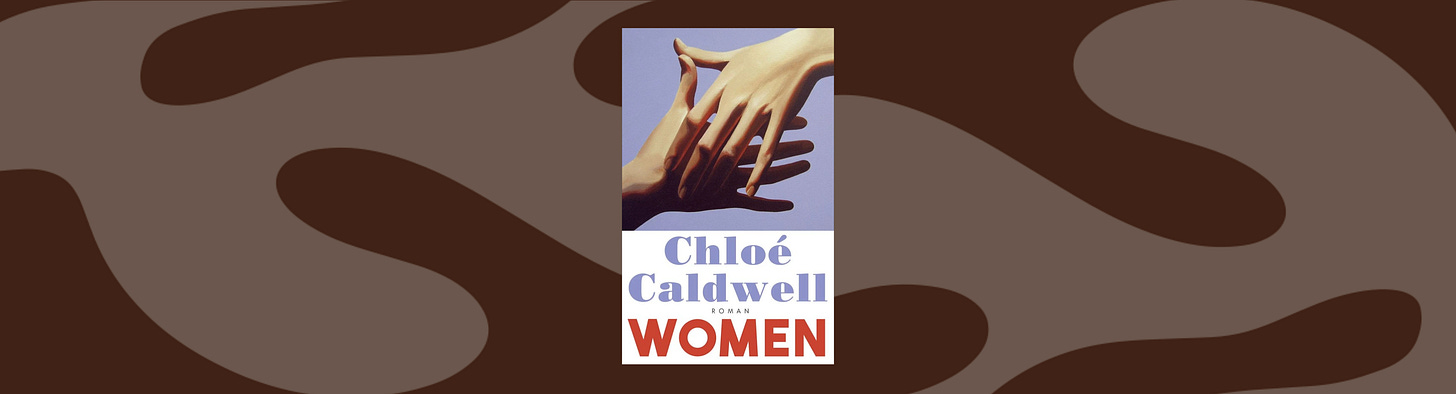

Women: A Novella, Chloe Caldwell

I read Women while lying in a hammock in Denmark. It was a sunny day, and I had nothing on but my underwear, and sticky peach juice on my fingers. I am increasingly drawn to women writers who experiment with form and seem hell-bent on ruining their own reputation. These are my women.

For me, this book was a kind of study in craft. An examination of how to tell a story that isn’t neatly redemptive, how to capture obsession without apology. Caldwell writes about a woman falling in love with another woman for the first time. It is a story of fixation, unraveling, and the humiliation of wanting more than you’re being given.

The cadence, restraint, and omission is what captivated. It made me realize that sometimes the most compelling story is that one that sits inside one singular emotion until it transform. Women reminded me that writing — like desire — doesn’t need to resolve. It just needs to feel true while it’s happening.

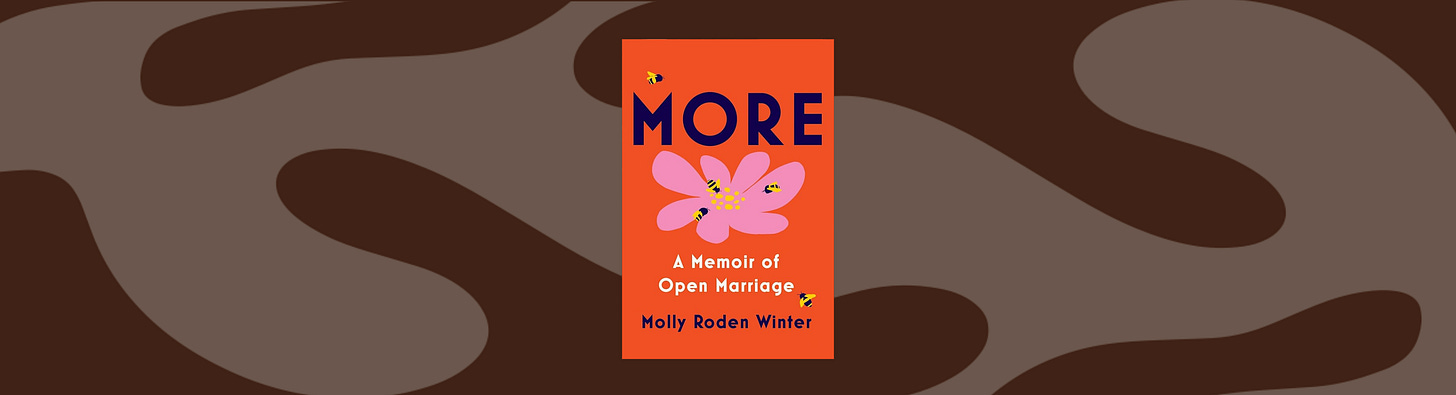

More: A Memoir of Open Marriage, Molly Winter

This is a memoir about open marriage. I’ve been exploring non-monogamy conceptually and practically this last year, and was interested to what a woman lay out her own experience of it real-time. Eve Babitz writes, “If you’re afraid it’ll ruin your reputation, it’s probably the best thing in the piece,” and my experience is that potentially reputation-ruining writer is where the gold lies. And Molly Winters definitely digs for gold in this memoir.

She is a wife and mother in her forties opening her marriage, guiding less by fantasy and more by dissatisfaction. It would be frighteningly easy to disregard this as a last-ditch effort and scream, “Just get a divorce already!” But that reaction leaves little room for nuance.

What I found my fascinating from her experience was the psychological choreography of non-monogamy. Not the apps, and rules, and jealous, and fucking. But the psychology. She is constantly toggling between freedom and fear, guilt and aliveness. She does not glamorize anything, but she also does not apologize either. She writes about wanting more even when she already has enough.

I kept thinking about how desire tends to arrive in moments of stability, and how often we reach for transgression when life feels too still. Or is that just me? Winters own reflections on motherhood and erotic renewal made me consider my own threshold for risk and honesty.

The Dry Season: A Memoir of Pleasure in a Year Without Sex, Melissa Febos

A few months ago, a man I’d been seeing sent me an article about Melissa Febos’ new memoir The Dry Season. He’d made a joke about how we’d never survive a few weeks—let alone months—of celibacy.

The sweet irony is that I immediately ordered the book and ended up being moved beyond measure by Febos’ story, her writing, her honesty. In fact, so much so that I’ve now taken my own pause—three months without sex, dating, or even the smaller, stickier forms of attention-seeking that used to give me a hit of dopamine.

Febos writes about desire as a force both sacred and unruly, a biological pulse that can’t be reasoned with. “The desire that drove this endeavor was not rational,” she says. “I felt it in my body, like physical hunger.” I know that hunger—the kind that doesn’t point to a person so much as a direction.

For Febos, abstinence becomes a devotional practice. Her “dry season” becomes a laboratory for clarity and a way to study desire without drowning in it. She learns that restraint is a way of courting desire more honestly. “An animal can be very hungry and not know for what,” she writes, “only in what direction it lay.”

Thank you. Some great recommendations, and oh so important, as the challenges that await us all seem daunting.

Adding so many of these to my must-read list. And would say - get yourself a copy of The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy asap and then let’s discuss!!