Last night I was draped over the orange velvet couches at Sociale, a co-working space in Sidi Bou Saïd, talking to my friend Karen about oversharing. A few months back, I’d had a similar conversation with a stranger in a hammam in Marrakech, except she was naked and I was wrapped in a towel that kept falling off.

This year has been a continuous unfolding of kismet, and my meeting Karen was no different. We are what I call cauldron sisters, brewed in the same primordial ooze. Meeting each other felt like a long exhale. There you are.

In February, I saw a $50 flight to Tunis and booked it immediately. I was supposed to be saving money — given that I haven’t paid rent in over a year, you’d think I’d have amassed a decent sum by now. I have not. Money is slippery like that.

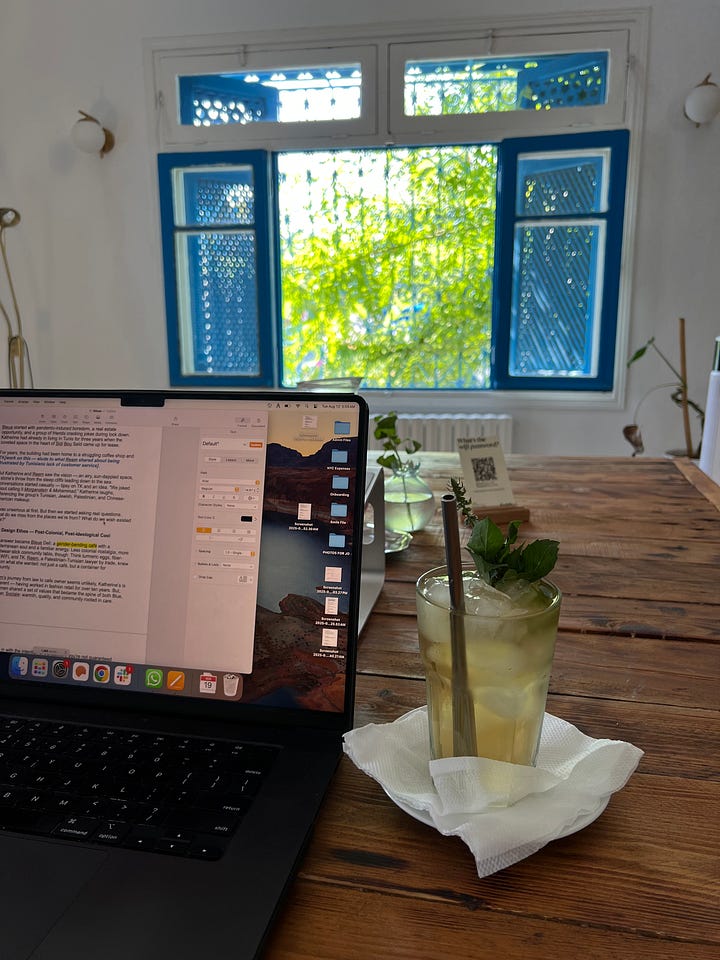

That’s the thing about wanting to go everywhere: a cheap ticket is reason enough. I landed with no plan except a half-remembered history lesson about the fall of Carthage. A friend told me, “Go to Bleue Deli. Have a coffee. Find Karen.”

Three hours later I was at a cobalt-blue table with Karen, the smell of cardamom and cigarette smoke weaving between us. We were swapping stories about our lives in Tanzania, the Cayman Islands, Paris, Sousse. Writing (me) and photography (her). Abuse and recovery. How differently and yet exactly the same we’d been taught to distrust ourselves.

Somewhere in that conversation I confessed my little longing, “I want to write the breakup/cult story for The Cut.” She nodded. “Well, it looks like my years of researching cults might actually be helpful to someone.”

A few days later in London, I went straight from the airport to the only coffee shop in the neighborhood that wouldn’t kick me out on a Sunday. Most coffee shops in London and Paris are anti-laptop, which I generally respect — until it’s me who wants to sip espresso and work. But not this one. This one smelled like burnt toast and floor cleaner, and I drank orange juice, flat whites, and sparkling water in a kind of chaotic rotation until my laptop battery gave up.

That mess of words became my first draft for The Cut.

Every important conversation in my life has started with me feeling a little scared, a little uncertain, or wildly overdressed for the occasion.

Last week, I got the preview link from my editor at The Cut. I sat on a log in London and cried. Then I got a text from a man trying to woo me into a threesome. I texted Karen: I’d rather just have sex with him, I tell her. But that feels wrong because he has a girlfriend.

Karen texted back: Two wolves inside me. One is horny. The other is justice-oriented.

Last night on the couch I told her, “I’m about to post something really unhinged.”

She laughed. “I love how little you care.”

And I do care, but not in the way I used to — not in the way that polices which parts of myself I share. We are now living in the hyper-confessional internet era. Radical banality. People are filming themselves crying and crashing out. What used to be cringe is cool. I saw a man in the medina wearing a shirt that said Live Laugh Lemon and I’ve been thinking about it ever since. I feel like we’ve all run out of fucks in the same week.

Everyone’s oversharing at such a high frequency that if I write about sex, grief, being burned by a relationship, or something strange I noticed on the bus, it just dissolves into the scroll. In a way, there’s freedom in shouting into the void about how horny I am all the time.

Back in November, I wrote openly about sex for the first time. I was trying to tell the story of my time in Istanbul without mentioning the handsome, albeit bumbling, Turkish man who fumbled in my pants for five seconds before saying, “You can cum now, baby.”

It was mortifying and hilarious, but essential to the story. Without it, the rest didn’t make any sense. And I can’t imagine Babitz or Didion omitting a scene just because it might make their uncle uncomfortable.

Since then I’ve been leaning into this edge — writing about desire, pleasure, awkwardness. I’m tired of performing that calibrated internet femininity: pure but sexy but not too sexy, hinting at intimacy without admitting to it. I don’t want to worry about what my father or an old boss or some bored stranger thinks.

I want to write with the wild freedom of women like Miranda July, who, in her novel All Fours writes about loving a man’s penis so much she wanted to “pitch a tent next to it and live there forever.”

I’m interested in writing that’s raw and uncomfortable. The kind that makes your cheeks heat. Eve Babitz said, “If you’re afraid it’ll ruin your reputation, it’s probably the best thing in the piece.” I might tattoo this on my forehead.

As Karen stood up and began rearranging the throw pillows on the clementine-colored couch, I sat up.

“It’s not that I don’t care,” I said. “It’s that I’ve decided to only care about a select few people’s opinions of me.”

I didn’t say the rest — that she has become one of those select few.