Women At Rest, Women In Power: Suzanne Valadon and the Female Gaze

On Female Autonomy, Art as a Mirror, and the Radicality of Rest

I am wandering through the arterial streets of Paris, the grey clouds painting themselves across the city and slate rooftops, and I see an advertisement for a Suzanne Valadon exhibit at the Centre De Pompidou. I feel her name echo somewhere in my mind. I’d read about her in a memoir months earlier. Without much thought, I drop what I was doing and head towards the museum. You see, this is the life I want—one that prioritizes pleasure, leisure and the malleability to change one’s mind.

On my walk over, I listen to a podcast about her life—suddenly desperate to learn all the intricate layers of this woman’s story. A seed may have been planted many months before, but it felt like it had just thrust through the soil and I feel a voraciousness I can’t quite explain.

When I arrive at the exhibit, I am surrounded by mostly older Parisians. I feel a giddy anticipation as the curving queue brings me closer and closer to the entrance.

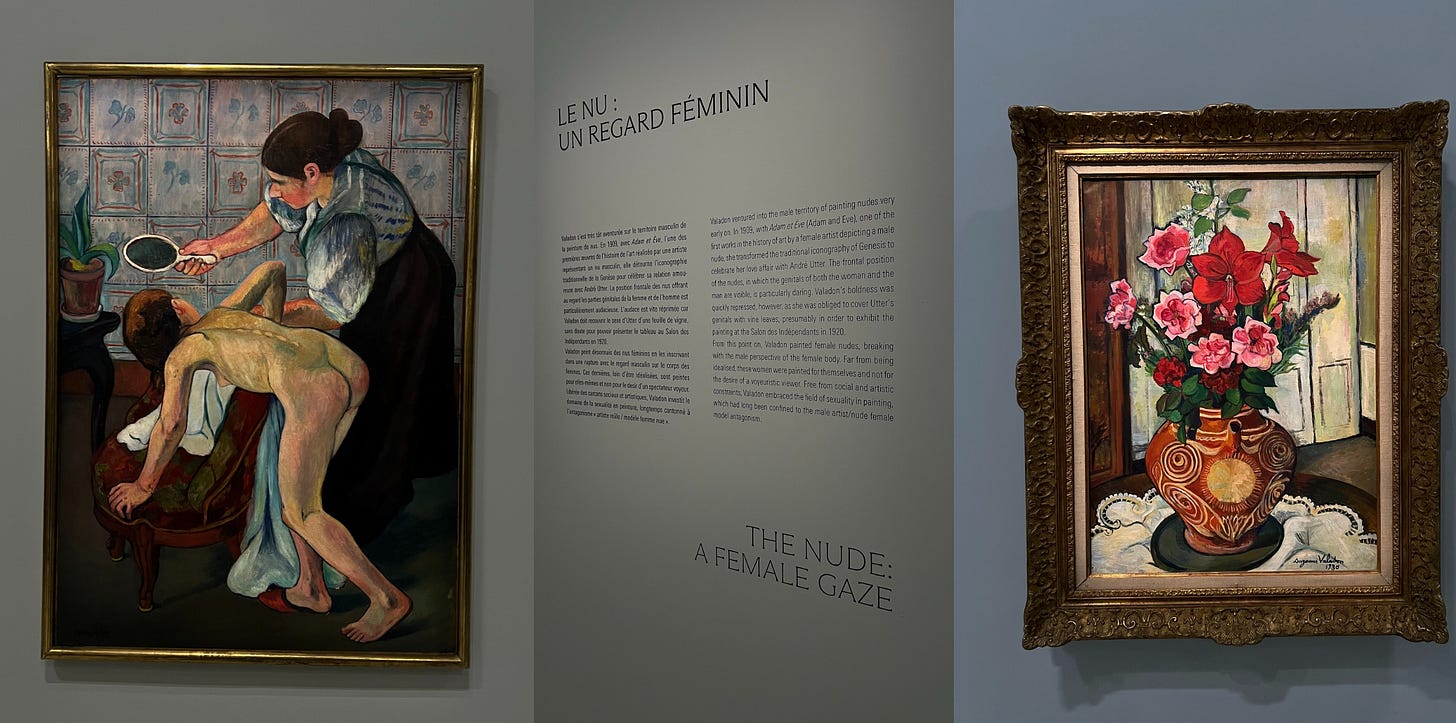

The first thing I see when I walk into the exhibit is arguably Valadon’s most famous painting, The Blue Room. The woman in the painting—soft, solid, sprawled out on the bed like she owns every inch of it—isn’t waiting for anyone. She isn’t presenting herself. She isn’t a muse. She just is.

She is wearing striped blue pajamas, smoking a cigarette, legs crossed at the ankles, belly rounded under the fabric. She is a woman with nowhere to be; no one to please. Her gaze is somewhere else, completely unbothered by the fact that she is being looked at. There is a lack of self-consciousness in her body that I think all women aspire to; an ease that we desperately crave.

The room is saturated with blue. The brushstrokes aren’t delicate, the contours aren’t smoothed. She is not made to be beautiful, but rather she is made to be real.

I stand in front of her and feel an electric awareness in my own body. How often have I held myself in the opposite way—pulled in, arranged, adjusted? I think of the women before me, my mother, my grandmother, all the women who were told to shrink, to be pleasant, to make themselves palatable. And then I think of her—lounging in her own fleshiness, uninterested in my gaze, uninterested in anything but her own comfort.

I keep walking, knowing I am about to meet all of Valadon’s women. But I am already quite clear, these weren’t going to be just paintings. They are going to be messengers, mirrors, and permission slips—an initiation into the depth of the female gaze.

Suzanne Valadon knew what it meant to be seen. Before she was a painter, she was a model—a body studied, translated through the hands of Renoir, Degas, and Toulouse-Lautrec. She spent years as an object of the male gaze before she turned her brush to canvas. But when she did, she upended everything.

Valadon had no formal training, no prestigious schooling. What she had was grit, an insatiable hunger, and a life that refused containment. Born into poverty, raised by a single mother who worked as a laundress, she climbed into the art world by force of will. By sixteen, she was posing nude for Paris’s great artists. By twenty, she had a child—unmarried, unwilling to name the father. By thirty, she was painting, defying the polite conventions that would have left her cast aside as just another forgotten muse.

But this woman was never meant to be lost to the pages of history. She drank with Toulouse-Lautrec, held her own in Montmartre's debauched cafés, and painted with the kind of ferocity and irreverence that made men uncomfortable. She married a financier, briefly playing the role of bourgeois wife–only to abandon it all for her twenty-year-old son’s best friend, a man half her age. She was chaos and hunger, indulgence and sharpness, a woman who never asked permission and spent her life honing her seeing eye. Is it any wonder that I was so enraptured by this woman?

It is this seeing eye that helped make Valadon’s women so different. They are not arranged, not adorned, not offered up. Her brushstrokes do not idealize. They reveal. Her women are not desirable, they are undeniable. They sit with their legs spread, their bellies soft, their arms folded across their chests—not hiding, but not inviting either.

Standing in that gallery, surrounded by these women, I felt something I hadn’t realized I had been longing for: a different way of seeing. These women had given up the senseless pursuit of needing to be understood. They were neither virgins nor vixens; no symbols or stories projected upon them. They were lived-in, autonomous.

I thought about my own embodiment and solitude. The way I have spent years unlearning the instinct to arrange myself—on couches, beds, in mirrors, in the presence of others. How often have I softened my body, shrunk myself inward, subconsciously rehearsed the pose of a woman made palatable? And here were Valadon’s women, rooted in themselves, with no impulse to please.

It’s easy to see why Valadon’s work was radical at the time, and perhaps startling to realize how radical it still seems. Even now, women are rarely given permission to exist without being watched, judged, assessed. We are told that our power is in our desirability, that our bodies are stories meant to be told by someone else.

But Valadon, well ahead of her time, rejected this premise entirely. She did not paint women as ornaments or symbols—she painted them as forces. As beings.

In her world, women are not objects of pleasure or projections of fantasy. They are bodies that carry life, weight, time. They are themselves, and that alone is enough.

Ultimately, art—which is to say paintings, literature, music, or anything in between—serves as a conduit to reveal a part of our true nature. It lays bare our longing, our grief, and our unadulterated desire. I have not, historically, been so viscerally awake to this truth.

Yes, I had the privilege of a childhood that allowed me the opportunity to wander art museums on weekends and learn the names of great painters—all men—from the tiny plaques on the walls. On Friday afternoons as a teenager, I used to wander into the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, and sit in front of a massive Albert Bierstadt painting depicting the Sierra Nevadas. I’d sit there for hours sometimes, losing myself in the expanse of the painting. The idea of being moved by artwork is not foreign to me.

But something has been different lately. I am seeing the threads between the artwork—the connective tissue between the paintings and the stories that they tell. All of the selves being revealed.

Shortly after visiting Valadon's women, I was in Vienna, Austria, and I went to see Gustav Klimt’s work at the Belvedere Palace. While the crowds gathered around his most famous painting, The Kiss, I found myself drawn instead to Judith and the Head of Holofernes.

Judith—bare shoulders, gold-draped body, head tilted back in something like pleasure, lips parted just so. She is powerful, yes. But it is a power that is seductive, theatrical—one that is meant to be seen. Klimt paints her not just as a woman who has vanquished a man but as a woman whose power is made erotic, dangerous, an object of fascination.

As I stared into her eyes, I thought about Valadon’s women. How different they were. How unbothered. How uninterested in being interpreted, feared, desired. Klimt’s Judith is powerful because she is both seductive and menacing—a modern day Medusa, her power defined by the tension between allure and danger. She exists to be looked at, to be reckoned with.

Valadon’s women are powerful because they are neither. They do not seduce, nor do they resist. In mythology, they would be the virgin goddesses—not in the modern, reductive sense of virginity as purity, but in the ancient sense of autonomy. Goddesses like Artemis, Hestia, and Athena were called “virgin” because they belonged to no one; they were self-possessed, whole unto themselves. This is the kind of power Valadon’s women hold: a radical self-containment, an interiority untouched by the need to be seen in any particular way. I think, perhaps, this is what I aspire to more than anything else.

In contrast to the women of Klimt or the muses of the male Impressionists, who often exist in relationship to the viewer—whether as objects of admiration, desire, or even narrative tension–Valadon’s women do not invite interpretation. They are not warnings, not fantasies, not sirens or saints. They are bodies that have lived and have made their own meaning.

And that left me with a question: is power only legible when it is either seductive or threatening? Is a woman only allowed to take up space if she is resisting or enchanting?

From the femme fatale archetype to the ‘girlboss’ era, power is still often packaged as either seduction or dominance. But Valadon’s women suggest something entirely different: a power that is not performed, but simply embodied. For so long, power has been seen through the lens of the male gaze–something that must be wielded. But what if it is simply held? What if the most radical form of female power is not seduction or resistance, but peace? A power that needs no explanation, nor performance.

I carried these questions with me as I left the gallery, out onto the streets of Vienna, and wandering the quiet Danube at dusk, And then, a memory: sitting alone at a cafe in Paris, coffee cooling on the table, the city moving around me, the soft weight of my own body settling into the chair. No one waiting for me. No one watching me. No one needing anything from me.

Power, I realized, is this too. A woman in solitude, at ease, simply existing.

This is what Valadon’s women know—and what they offer back to us: the ability to be more than symbols, more than myths, more than muses. To be ourselves—without explanation.